Cheat Code for a Lightning Fast Front End: Building an Optimistic UI

How we can leverage the optimistic UI pattern for maximum performance in our app

In the never ending pursuit of building faster and faster web apps, there are no options off limits. We split our databases to optimize for reading and writing, make our services scale up and down with demand and have complex caching strategies on top of all of it.

Despite that effort, we still show our users a spinner every time they click a save button. No matter how much we optimize on the back end, that delay will be noticeable to our users. We've trained them to click and wait.

When you think about it though, do we really need to? If our API is reliable and fast, we're inconveniencing our users on the 1% chance something will fail. Instead of doing further optimizations to the API to make our app feel fast, there's a different approach we can take that's almost like cheating. When a user clicks a button, we no longer wait for the request to complete. We assume it's going to be successful.

So what does that mean in practice?

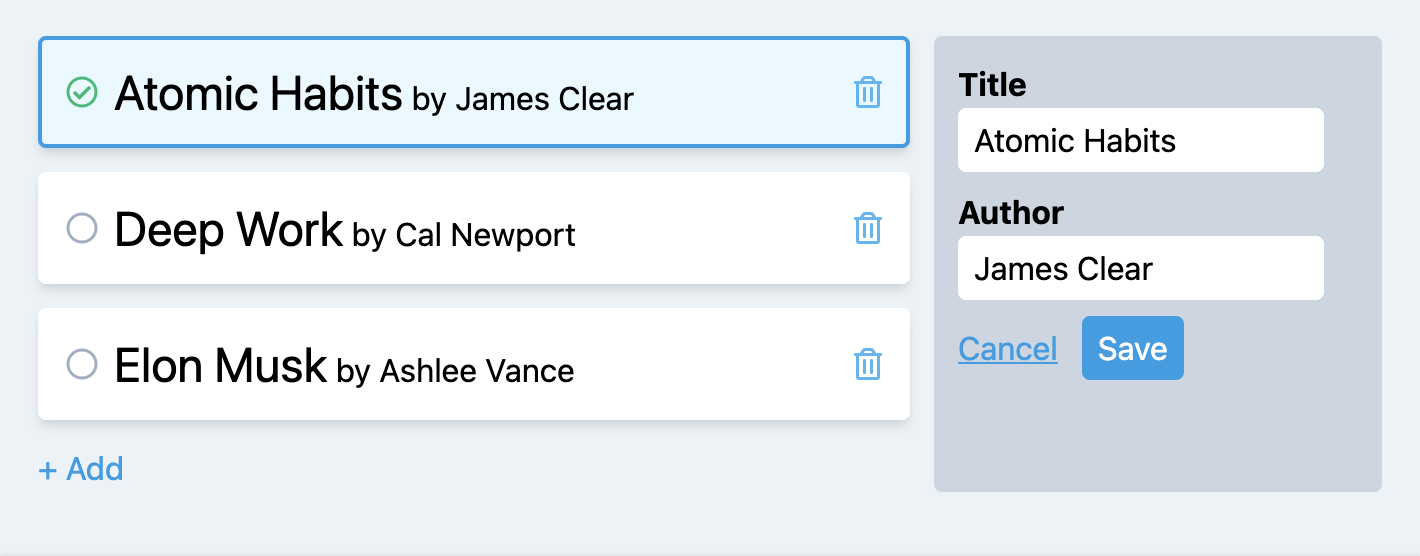

When the user clicks the save button, boom. Green check. Instant feedback. The delete button? One click, and immediately it's done. No spinner, no delay, no nonsense. We've moved the waiting out of the way, our users are more engaged and can now focus on their workflow completely. This is the essence of the optimistic UI pattern.

We see this in the wild all over the web with the most well-known example being the like button on just about any social platform.

Here's an example from Twitter. We've clicked the like button, and it's showing the change in the UI, but the Network tab tells a different story. Notice how every request is still pending.

The Sample App

To demonstrate applying the optimistic UI pattern, we will be going through a really simple app for managing a list of books. The user can add, edit, delete, and mark a book as their favorite. It's currently written in a "pessimistic" way, but we're about to change that.

The example code is written with React, but the pattern can be applied whether you're using Angular, Vue, Svelte or just Vanilla JavaScript.

Where NOT to Apply It

This pattern can be applied with POST, PUT, and DELETE requests, but the better question is when should we use it. We might not want to use this pattern in cases where:

- The API is applying validation that the UI is not

For instance, if we're deleting something that is potentially referenced elsewhere - The API has a tendency to be slow

If a particular endpoint takes a long time to persist changes, applying an optimistic update is not a good fit. Depending on how long an update takes, the user may have time to leave the screen and pull up a totally different record. If that update was to fail, we definitely don't want to have to pull them back into something they're no longer thinking about. As long as operation tends to complete in less than 2 seconds, it's okay to make it optimistic. - The API is unreliable

If an endpoint relies on an operation or third party service that has a higher failure rate, then it's not a good candidate for an optimistic update.

In short, we should only apply it to fast and reliable endpoints.

An Optimistic Toggle

The best place to start sprinkling in some optimism to our code is a toggle. For our app, we have a button to mark which book is our favorite. Currently the code for setting that data looks like this:

function updateFavorite(id) {

fetch(`/favorite/${id}`, { method: 'PUT' })

.then(() => setFavoriteBookId(id));

}

We make the update and when it completes, we set the favorite book id.

Now let's make this go a little faster.

function updateFavorite(id) {

setFavoriteBookId(id);

fetch(`/favorite/${id}`, { method: 'PUT' });

}

We skip the waiting and immediately set the favorite book id, and then we fire off an API call to persist it.

Optimistic Delete and Edit

Delete and edit are the same story when it comes to applying this pattern. We update state and then make the API call.

function deleteBook(id) {

// delete the book from state

setBooks((prev) =>

prev.filter((book) => book.id !== id)

);

// fire off our request

fetch(`/books/${id}`, { method: 'DELETE' });

}

function updateBook(book) {

// update the book in state

setBooks((prev) => {

const bookIndex = prev.findIndex(

(b) => b.id === book.id

);

return [

...prev.slice(0, bookIndex),

book,

...prev.slice(bookIndex + 1)

];

});

// fire off our request

fetch(`/books/${book.id}`, {

method: 'PUT',

body: JSON.stringify(book)

});

}

An Optimistic Create

The most challenging usage of the optimistic UI pattern is when creating a record. With updates and deletes, we have all the information on the client side, so updating state before we make an API call is no big deal. But with a create, there's one key piece of information we have no choice but to wait on: the new record's ID.

How we go about it is largely dependent on the UX of our screen. In the case our book app, we just have a small list of books with an inline edit form, so our dependence on the ID is so that we can render it in the list.

To get around it, we generate a temporary ID for the record while we wait on the API and then update it to the real ID once we have it.

function addBook({ title, author }) {

// generate a random negative id

const tempId = generateTemporaryId();

const book = { id: tempId, title, author };

// immediately add the book

setBooks((prev) => [...prev, book]);

fetch('/books', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify({ title, author })

})

.then((res) => res.json())

.then((newBook) => {

// update the id of the book after the POST completes

setBooks((prev) => {

const bookIndex = prev.indexOf(book);

return [

...prev.slice(0, bookIndex),

newBook,

...prev.slice(bookIndex + 1)

];

});

});

}

Handling Errors

Now, if you've gotten to this point, you're probably wondering how we handle when things actually fail. Since we've essentially been lying to the user, we need a good way to confess when things aren't so optimistic.

The big advantage of an optimistic UI is getting a user engaged in our app and into a flow state. They're no longer thinking about how our app is working. They're 100% focused on the task at hand. When we show a user an error, it is pulling them out of that flow, and we need to take great care in how we help them resolve the issue.

In some cases, like setting a favorite, it may not be worth it to show that it didn't succeed. Keeping user engagement may be priority over highlighting an unimportant failure.

In fact, Facebook does exactly that with their like button. With WiFi turned off, it will appear to let you like things, but after a refresh, you'll discover nothing actually saved.

UX Options When a Request Fails

No Error Message

For nonessential operations where user engagement is more important, we can forgo the error message.

Toast Notification

Having a clear error message show as part of our application's notification system should be the most common error handling method. Even if the user leaves the screen, we need to make sure the error is still able to show.

A Modal or Toast Notification with Buttons

In certain cases, we need to give the user options to resolve the error. They could have spent a lot of time creating or updating a record, and if they have already left the screen, we need a way of informing them of the error and giving them some options as to what they can do.

A modal would be the most urgent option to stop a user in their tracks, while a notification with buttons would be a little less jarring.

Depending on the cause of an error, a button to retry would be helpful. Timeout errors and system maintenance can certainly cause an HTTP 500 or 503 response from time to time, and a retry could resolve the issue outright. However, the retry button should not use an optimistic update. We need to give the user confidence their information is saved correctly this time, so a spinner on the button would be appropriate here.

The other option is to take the user back to the screen they were on with all their information filled out again. At that point, they can correct any issues, or in the worst case, save off their responses to another application until the API defect is resolved and they can re-enter the record.

In any case, we need to do everything we can to make sure our users don't lose their work.

Now, let's see how we can apply this to our book app.

Set Favorite

To be a little more honest with our users, we're setting the favorite book back to the original one in case the update fails. For this case, we're choosing to not show an error message.

function updateFavorite(id) {

const previousFavorite = favoriteBookId;

setFavoriteBookId(id);

fetch(`/favorite/${id}`, { method: 'PUT' })

.catch(() => setFavoriteBookId(previousFavorite));

}

Delete

For a delete, the simplest thing we can do to get back to a correct state is similar to what we did for setting the favorite. We save a copy of the books and roll it back if it fails. To inform our users, we're going to show an error notification.

function deleteBook(book) {

const previousBooks = books;

// delete the book from state

setBooks((prev) =>

prev.filter((b) => b.id !== book.id)

);

// fire off our request

fetch(`/books/${id}`, { method: 'DELETE' })

.catch(() => {

// roll it back

setBooks(previousBooks);

// show an error

toast.error(

`An error occurred deleting ${book.title}`

);

});

}

Create / Update

For create and update, we're going to handle errors in the same way. After a failed POST, we just need to delete the book out of the books array.

function addBook({ title, author }) {

// generate a random negative id

const tempId = generateTemporaryId();

const book = { id: tempId, title, author };

// ...immediately add the book...

fetch('/books', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify({ title, author })

})

// ...

.catch((error) => {

// delete the newest book

setBooks((prev) =>

prev.filter((b) => b.id !== book.id)

);

// inform the calling code there was an error

throw error;

});

}

And for a failed PUT, we roll back the books to the original.

function updateBook(book) {

const previousBooks = books;

// ...update the book in state...

// fire off our request

fetch(`/books/${book.id}`, {

method: 'PUT',

body: JSON.stringify(book)

})

.catch((error) => {

// roll it back

setBooks(previousBooks);

// inform the calling code there was an error

throw error;

});

}

Notice how in both catch handlers we throw the error again at the end. This is so that the calling code can do more application-specific logic to handle the error.

In the onSave of handler for our book form, we save the book, and if there's a failure, we show a custom error toast that allows the user to retry saving the book.

function onSave(book) {

setSelectedBook(null);

// add or update the book

const promise = book.id >= 0

? updateBook(book)

: addBook(book);

// handle errors in the same way for add and update

promise.catch(() => {

toast.error(

<ErrorToast

message={`An error occurred saving ${book.title}.`}

// reset the book as selected, so the user

// can try again

onTryAgain={() => setSelectedBook(book)}

/>,

{ autoClose: false }

);

});

}

Here's the full CodeSandbox to see everything from end to end.

Summary

- The optimistic UI pattern assumes our API calls will succeed and uses that to make our app feel extremely fast. This increases engagement and helps our users get more done.

- It's best to apply this pattern to endpoints that are fast and reliable.

- When it comes to handling errors, think through the UX to determine the best way to inform the user and make sure they don't lose any of their work.

How are you using the optimistic UI pattern in your app?